Client Story: Innovation by Design, Not Declaration

How network analysis and behavioral design helped a mature organization rebuild for both operational excellence and breakthrough innovation

At a Glance: A national bank with thousands of employees faced a quiet slowdown in innovation. Ideas grew safer, projects slower, and silos deeper. Our analysis showed why: growth had rewired the bank’s networks and culture in ways that rewarded predictability over boldness. By redesigning both structure and incentives, we helped create a space where breakthrough ideas could flourish again.

A Subtle Shift

The signs were subtle at first. A large national bank, proud of its history of innovation, began to notice a watering down of ideas. Project deadlines dragged. Bold, market-changing concepts arrived smaller, safer, and less ambitious than at its founding. Nothing in the headlines suggested crisis. Earnings were healthy. Market share was steady. Yet inside the walls, something was shifting. The culture that once took risks and delivered breakthrough products was now producing incremental improvements at best.

Long standing executives were surprisingly blind to the shift, which isn’t uncommon. Cultures drift over long periods, often without explicit direction. No one said “be more conservative” or “take fewer risks”. The bank continued to invest in R&D and regularly recruited external talent to inject fresh ideas. Our Cultural Due Diligence showed employees still believed in the firm’s innovative DNA.

Yet the energy wasn’t translating into outcomes.

The turning point came when the firm hired an outside executive from a smaller, bolder competitor. In her first weeks she declared, “You’re not innovative.” The comment landed sharply, crystallizing what decades of drift had obscured. The symptoms were becoming visible. The cause, however, was harder to see.

Why Growth Changes Behavior

The problem wasn’t that talent or creativity had disappeared. Our due diligence surfaced two forces working together.

The first was behavioral. As firms mature, there is a natural tendency to protect gains and avoid risks that might jeopardize market share. Employees adapt quickly to the signals around them: long approvals, heavy oversight, and incentives tied to efficiency. The rational choice becomes to play it safe.

The second was structural. Growth demands functional hierarchies. They afford specialization and operational efficiency, but they weaken cross-pollination. Teams become excellent at execution within their own domains, yet more distant from each other.

It was growth itself that quietly reshaped the organization’s internal wiring. Both behavior and structure were nudging the firm from nimble to conservative.

As the bank expanded from a few hundred employees into the thousands, it evolved from an open, collaborative culture to a segmented, siloed one. Functions like product, technology, and marketing optimized for efficiency within their own domains, but connections across them weakened.

Larry Greiner’s classic model of “evolution and revolution” captures the cycle well: each stage of growth solves one problem while sowing the seeds of the next. For this bank, functional silos delivered scale and predictability. But they also triggered a crisis of coordination. What once enabled speed and creativity now slowed both down.

Sidebar: Open vs. Closed Networks

Not all networks function the same way. Sociologists describe networks in two broad ways, both important for different reasons:

Open networks are wide and redundant. They move information quickly across large groups and reduce risk by ensuring no single point of failure. These networks are essential for scale, keeping large organizations aligned, ensuring compliance, and maintaining predictable outcomes. Firms like Amazon, Toyota, or Procter & Gamble thrive on openness to stabilize performance at scale.

Closed networks are smaller, high-trust, and often insular by design. They create the conditions for speed, risk-taking, and deep collaboration. Pixar’s “Brain Trust,” Bell Labs in its prime, and Google’s X division show how closed networks can protect fragile ideas long enough to grow.

Neither system is sufficient on its own. Open networks stabilize what already works. Closed networks spark what comes next. The challenge is balance: protecting closed networks so they can flourish, while ensuring open networks are strong enough to carry successful ideas forward. Lockheed Martin’s Skunk Works remains the classic example: a closed team producing breakthroughs, embedded inside an open system that could scale them.

What the Network Revealed

In the bank’s earlier years, collaboration was informal and ideas flowed freely. As an upstart taking on larger competitors, risk was part of the game. Teams were small, networks open, and connections redundant. That redundancy, while inefficient, gave ideas multiple paths to travel.

As the organization grew, layers of hierarchy and formal structures narrowed those pathways. Influence became localized. Good ideas had fewer routes—and more complicated ones—to reach decision-makers.

Sociologists remind us that open networks are ideal for stability and scale, while closed networks are better for experimentation and risk. Both are valuable, but they serve different purposes. The trouble comes when an organization tilts too far in one direction. At the bank, open networks multiplied as it scaled. That was good for reliability. But it came at the expense of the small, interdisciplinary circles where breakthrough ideas emerge.

Employees responded rationally to the signals around them. Approvals were long, oversight heavy, and incentives tied to efficiency. Riskier ideas carried reputational cost, while incremental improvements earned recognition. Over time, what executives once called “Big I” innovation gave way to “little i” tinkering. The imagination was still there. What had shifted was the behavioral environment that determined which ideas felt safe to advance.

To test these dynamics, we deployed Organizational Network Analysis (ONA). Networks helped us see the structure of the bank’s teams—how communication, trust, and influence flowed. The behavioral lens helped us interpret why: which incentives, oversight practices, and risk signals nudged people toward safe choices. Together, these tools explained not just what was happening but how to design something different.

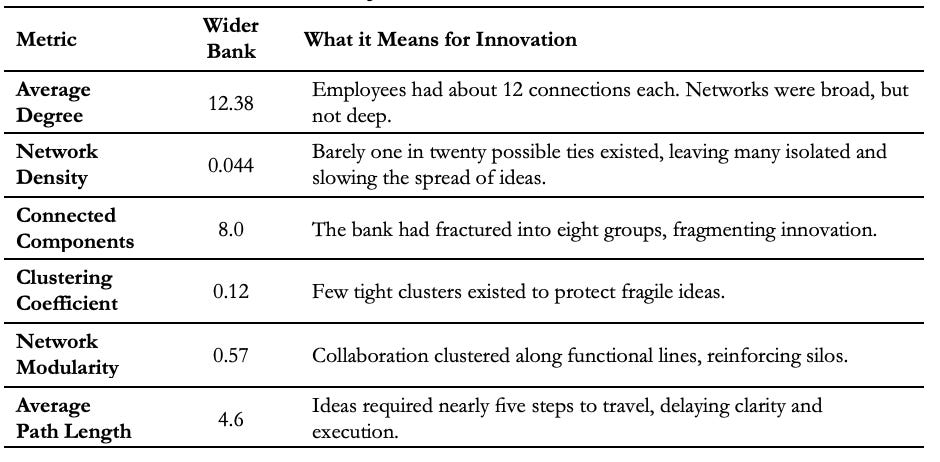

The metrics told the story:

Table 1: National Bank’s Network Dynamics

The network was optimized for control and efficiency, not for creativity. What helped the bank scale was now stifling innovation. And because behavior follows structure, employees adjusted accordingly — choosing safe bets over bold ones.

Designing a Space for Bold Ideas

The fix was not to overhaul the entire company. That would have been both unnecessary and damaging to operational efficiency. The breakthrough was to create a deliberately closed network inside the larger open one.

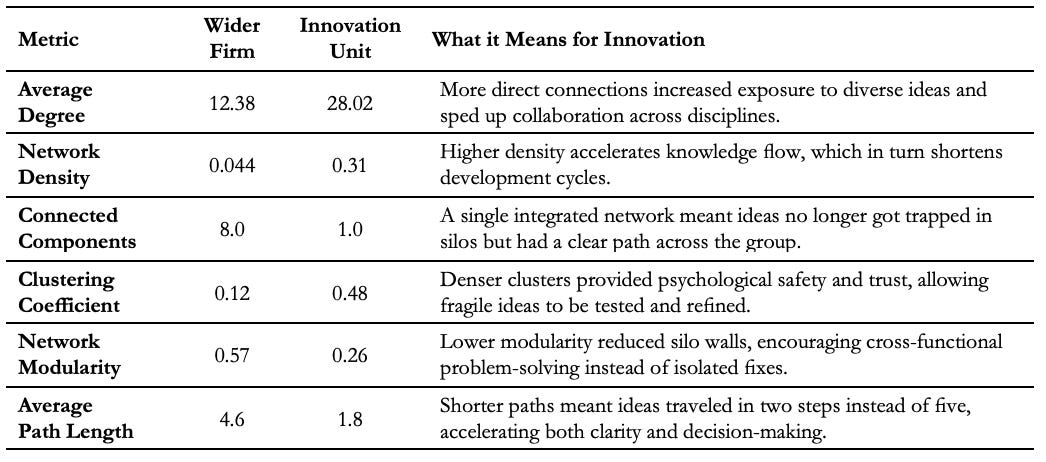

Drawing inspiration from Skunk Works, we helped design and launch a dedicated innovation unit. The group was ring-fenced from the governance and budgeting systems of the core business. Membership was cross-functional—technology, product, risk, marketing—and chosen not only for expertise but for proven collaborative disposition.

The design rested on two layers. Structurally, the wiring was different: tighter connections, fewer silos, and shorter paths that let ideas move quickly across disciplines. Behaviorally, the rules changed as well: oversight was lighter, success was measured in learning as much as outcomes, and incentives rewarded long-horizon bets rather than short-term efficiency. Structure gave the team speed; behavior gave it permission. Together, they created conditions that neither alone could have sustained.

Patent filings became the key metric. Early signs suggested filings would triple within the first year. Concept-to-commercialization looked to reach 2–3%, strong by innovation portfolio standards.

Equally important, the unit restored legitimacy to bold experimentation. Employees across the bank could once again see ambitious ideas being taken seriously. That visibility signaled that exploration had a place alongside efficiency.

Table 2: The Innovation Unit’s Network Dynamics

With structural and behavioral design working together, the unit created the conditions for Big I innovation without undermining the efficiency of the core. This dual-lens approach is critical: metrics alone diagnose the wiring, but behavioral design ensures the system evolves in the right direction.

Restoring the Balance

Innovation doesn’t disappear because people stop imagining. It stalls when networks and behavioral systems reward the safe path and close off the intersections where new ideas form. Growth makes this almost inevitable. Structures built for scale—silos, oversight, formal processes—slowly suffocate adaptability.

The lesson is not to choose between efficiency and creativity, but to recognize that each requires different conditions. Open networks provide stability at scale. Closed networks spark breakthroughs. Healthy organizations protect both.

Leaders should recognize when their system rewards predictability more than exploration, and rebalance intentionally. Symptoms like project delays or safer ideas are rarely failures of talent. They are signals of structural and behavioral misfit. The art lies in restoring equilibrium, often by building new spaces altogether, so creativity can breathe again.

About 3Fold Collective

3Fold Collective is a research and transformation firm that helps organizations close the gap between strategy and execution. We combine behavioral economics and organizational network analysis to make culture visible, measurable, and actionable. By diagnosing hidden dynamics and designing fit-for-purpose solutions, we help leaders align operational efficiency with innovation—so strategy moves from declaration to execution. Visit us at: www.3FoldCollective.com.

References

Amazon. (2020). Working backwards: Insights, stories, and secrets from inside Amazon. St. Martin’s Press.

Catmull, E., & Wallace, A. (2014). Creativity, Inc.: Overcoming the unseen forces that stand in the way of true inspiration. Random House.

Cross, R., & Parker, A. (2004). The hidden power of social networks: Understanding how work really gets done in organizations. Harvard Business School Press.

Greiner, L. E. (1998). Evolution and revolution as organizations grow. Harvard Business Review, 76(3), 55–68. https://hbr.org/1998/05/evolution-and-revolution-as-organizations-grow

Lockheed Martin. (n.d.). Skunk Works: A history of innovation. Retrieved August 31, 2025, from https://www.lockheedmartin.com/en-us/who-we-are/business-areas/aeronautics/skunkworks.html

Procter & Gamble. (2006). Connect + develop: A new approach to innovation. Harvard Business Review, 84(3), 58–66. https://hbr.org/2006/03/connect-and-develop-inside-procter-gambles-new-model-for-innovation

X, The Moonshot Factory. (2024). About X. Retrieved August 31, 2025, from https://x.company

Thanks so much sticking around to the very end. If your interest in piqued, you may to see how this plays out in other organizations. You may enjoy one of our critiques of current events. I might suggest reading how a subtle uniform roll-out at Starbucks evolved in to a lawsuit and thousands of employees walking off the job. You can reach that here:

When Strategic Execution Fails: Inside the Starbucks Uniform Debacle

At a Glance: Strategic execution is about minimizing the cost of adoption. Organizations today are struggling to implement their greatest strategies with 70% failing. In this article, we delve into the recent Starbucks’ fiasco to see how behavioral economics reveals why so many strategies fail to meet their goals.