The Hidden Organization: Mapping the Networks That Run Your Company

Strategic execution is the biggest challenge facing organizations. See how a growing field of sociological research is revealing a hidden network that drives results.

At a Glance: Strategic execution is the biggest challenge facing organizations today, with failure rates as high as 70%. In this article, we explore the origins of an increasingly popular sociological tool, and how network analysis mixed with behavioral economic thinking can reveal a hidden world where change and sentiment take shape.

Do some mid-level employees quietly nudge the organizaiton more than their C-suite executives?

In most organizations, the people who drive performance, innovation, and resilience don't always reside at the top of an official chart. They’re hidden in the web of relationships that, if revealed, would show how their power and influence ripple throughout an organization.

Let’s create a fictional organization to illustrate how this works in more complex, real-life situations. We’ll call our protagonist Maya. She wasn’t a manager. She doesn’t have a direct team, doesn’t hold a high-ranking title, and rarely appeared in leadership meetings. But, when critical questions came up about customer needs, process gaps, or implementation plans, Maya’s name always surfaced.

"Ask Maya," someone would say.

She worked in product management at a 700-person tech company, quietly sitting at the crossroads of engineering, product, and finance. She knew what was happening on the ground, how tools were used, and who had already solved someone else's problem.

No one had given her power. But everyone would seek her out.

Only after the company conducted an organizational network analysis did Maya become one of the most connected, trusted, and credible employees. In other words, she held social and political influence.

What Org Charts Miss (And Networks Reveal)

Org charts show who reports to whom, but not who makes things happen.

The real drivers of performance, innovation, and resilience often operate outside formal authority. These hidden connectors, brokers, and quiet leaders often shape outcomes in ways job titles alone can’t capture.

Modern network analysis helps surface these informal power structures. With the right tools, you can map how work flows, where trust or collaboration may stall, and employees hold leverage across teams.

In this article, we’ll explore where this thinking began, from its scientific origins and psychological foundations, to how it’s now being used in forward-thinking organizations to improve everything from retention to post-merger integration.

In the modern workplace, it’s not hierarchy that determines success. It’s the network.

The Unseen Power Structures That Shape Every Strategy

Every organization operates on two levels: the visible structure shown on the org chart and the informal network that actually gets things done: what organizational sociologists, like myself, often call the “hidden organization.”

We’re all familiar with the formal structure: executives at the top, managers in the middle, and employees reporting upward in neat, clean lines. This structure grants authority based on title, such as CEO, VP, or manager. However, these roles can also invite distrust, either because they senior roles often removed from frontline reality or carry the weight of institutional hierarchy.

Now, contrast that with the informal network. The web of relationships that flows beneath the chart. Here, authority isn’t assigned. It’s earned. It emerges through relationships and shared experience. In these networks, influence—like beauty—is in the eye of the beholder.

These unofficial leaders hold real sway, much like our fictional Maya. They may not appear on leadership rosters but have “earned authority.” Some may have titles. Many don’t.

The trouble is, we often don’t recognize these individuals until they’re gone. And when they leave? Work slows. Decisions stall. Bottlenecks surface.

That’s why network analysis—used for decades by sociologists, mathematicians, and intelligence agencies—have become essential for modern business leaders. It maps how influence ripples through an organization, who holds key knowledge, and where collaboration breaks down.

However, organizational network analysis (ONA) is just the starting point. It’s data that maps the landscape, but doesn’t tell us how to leverage that landscape. The real opportunity is learning how to tap these networks to spark change, accelerate trust, and build the kind of collaboration that charts alone don’t capture.

The Origins of Network Thinking and Why It’s More Relevant Than Ever

Modern network analysis draws from three foundational disciplines, each offering a unique lens into how influence works beyond the org chart.

Psychology: Mapping Social Power in Plain Sight

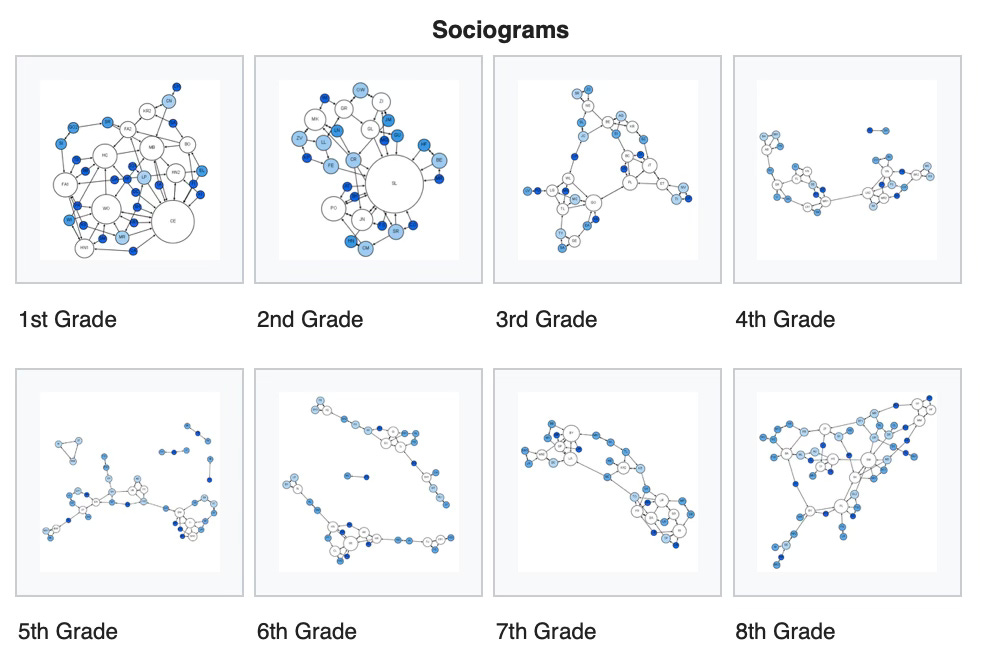

In 1934, pyscho-sociologist Jacob L. Moreno began charting classroom relationships to explore how friendship, trust, and even bullying shaped behavior. His research found that formal structures, such as teacher authority or assigned seating, often failed to capture informal power structures.

To surface these hidden dynamics, Moreno created visual diagrams that he called sociograms. These visualized the relationships among students and began to reveal who was trusted, who was excluded, and who quietly led.

Image: Jacob L. Moreno. Source: Wikipedia, Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0.

Moreno’s early maps were startling in their clarity. Even 1st graders identified central figures. By 3rd grade, cliques had formed. By 4th grade, students had sorted into defined clusters—some tightly knit, others isolated on the periphery.

While Moreno visualized power in small groups, anthropologists took a broader, cultural view.

Anthropology: Culture, Kinship, and Social Trust

In the 1940s, anthropologist Alfred R. Radcliffe-Brown studied tribal societies in Australia to understand how social structure (not just hierarchy) shaped power.

What he found was unseen at the time: power didn’t always reside with the official tribal leader. Instead, it mostly flowed through those who managed inter-group relationships. These were the individuals trusted to pass messages, settle disputes, or preserve rituals. Kinship ties, ceremonial roles, and social obligations created networks of influence that, in some ways, undermined formal authority.

In many communities, the person who understood and navigated the social fabric—not the one with the highest title—truly held power.

This anthropological lens revealed that influence often hides in group dynamics and customs shared by proximity, not institutional rank. It laid a conceptual foundation for modern network analysis, especially in cross-cultural or global organizations, where social norms and informal leadership can either strengthen or sabotage strategy.

Mathematics: The Hidden Geometry of Human Systems

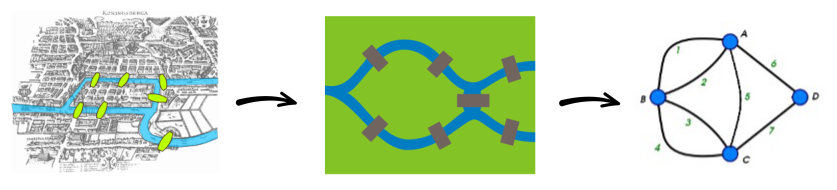

Long before “social networks” existed, mathematicians were solving problems of connectivity.

In 1736, Leonhard Euler tackled the Königsberg Bridge Problem, modeling land masses as nodes and bridges as edges. This gave birth to graph theory, the mathematical foundation for understanding how structure, not just content, determines movement within a system.

Image: Königsberg Bridge Problem. Source: Wikipedia, Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0.

Fast-forward to 1959: Paul Erdős and Alfréd Rényi applied probability theory to networks. Their models showed how connections in a social group form, grow, and concentrate. leading to the emergence of hubs of influence.

Erdős and Rényi’s legacy gives us the mathematical language to map and measure influence. Combined with the social and anthropological underpinning, we now have a modern toolkit used in everything from Google’s search engine to internal org charts.

Who Really Holds Power? A Look at Network Centrality

Leveraging these insights, we can now begin to see that in most organizations, power doesn’t just come from a title, but comes from where you sit in the network. Your proximity to others.

One key measure we use to measure proximity is called centrality, which measures how connected someone is: how often they connect others, and how many steps it would take to reach across the entire system. But power is more than just connection. It comes from access to novel information and the ability to bridge between disconnected groups.

Let’s go back to Maya.

Her degree centrality—or the number of people she directly interacts with—wasn’t particularly high. But her betweenness centrality is. This measures how often someone sits on the shortest paths between others, connecting people who might not otherwise collaborate.

Maya didn’t just know people, she connected teams. That made her a critical conduit for information, someone who enabled faster decisions and smoother coordination. Without her, communication between Product, Engineering, and Finance might have stalled or fragmented entirely.

Maya also has high closeness centrality, meaning she could quickly reach anyone across the organization in a few steps. This made her especially effective during the pandemic when remote work separated teams physically, Maya kept the network moving. She gathered updates, shared knowledge, and kept relationships warm.

Sociologist Ronald Burt introduced the idea of structural holes, which are gaps in the network where no direct connection exists. Those who bridge these gaps gain access to non-redundant, often novel information. In other words, they hear things no one else does.

If Maya could bridge the gap with, say, Sales—a team she wasn’t yet connected to—she wouldn’t just add another contact. She’d gain a new perspective. That’s where real power lies: the ability to see what others can’t and share insights no one else has.

Closing this gap allows for the free flow of information. And, especially where modern organizations are today, might lead to increased collaboration among teams, improving operating efficiency or drive product innovations. It’s the basis for what CEO is looking to achieve in our face-paced society: organizational nimbleness!

A Quick Guide to the Four Types of Network Influence

But network science doesn’t just show who has access, it helps us understand how that access could be leveraged to generate power, influence, and impact. To get there, we need to understand the behavioral side of networks: how relationships form, why people connect, and what makes some networks thrive while others stagnate.

How Relationships (Not Roles) Shape the Network

People don’t form workplace connections at random. Networks emerge from the way we build trust, share knowledge, and gravitate toward those we relate to, which is shaped by both psychology and social context.

Sociologist Pierre Bourdieu introduced the idea of social capital: the value we gain from relationships. Unlike money or skills, social capital doesn’t belong to any one person but lives between people. And social capital only works if it’s maintained. This explains why some relationships last while others fade, and why certain people become central to a network. Even if they hold no formal authority, like Maya.

This led to thinking of relationships in two very different ways:

Strong ties are the close, trust-based relationships we form with immediate colleagues or teammates. These connections offer stability, psychological safety, and deep knowledge sharing. They are the people you turn to when things get tough.

Weak ties, on the other hand, are more casual or distant connections. You don’t work with them daily, but they offer something different: fresh perspectives. Sociologist Mark Granovetter’s landmark theory, The Strength of Weak Ties, showed that people often find jobs through acquaintances, not close friends. Why? Because weak ties connect us to new ideas and networks we wouldn't access otherwise.

In organizations, innovation often moves along these weaker ties, jumping silos, challenging groupthink, and bringing in outside energy.

But networks are constantly evolving. And that’s where network structure matters:

Density shows how tightly connected people are. Dense networks spread information quickly, but can also become echo chambers where nothing new gets in.

Centralization shows whether influence is spread out or concentrated in a few key people. Centralized networks move fast, but are vulnerable if a central person leaves.

Clustering happens when small groups talk mostly to each other. It can foster trust, but block new thinking.

A 2018 study by Kumar et al. looked at echo chambers on platforms like Twitter (now X). People inside these clusters mostly reinforced the same ideas creating a perfect example of dense, strong-tie networks.

But when someone bridged between groups—even accidentally—new ideas spread. These weak-tie connections acted as unexpected pathways for influence and information.

Turning Network Data Into Business Action

Seeing Resignations Before They Happen

Managers and HR leaders are now able to identify which employees are more likely to leave. Employees on the social and political fringes of an organization, have a significantly higher probability of leaving in the next six months. Research shows that employees reduce their interactions materially prior to departing.

In short: people quit socially before they quit physically.

Similarly, some organizations have begun using network surveys to detect early signs of disengagement that can better inform the roots of disengagement better than traditional Employee Opinion Surveys. Research shows that network-based insights can predict over 70% of voluntary departures compared to just 48% accuracy using traditional tools like performance ratings or engagement scores.

The signals are subtle but powerful: decreased meeting attendance, shorter email responses, and fewer new connections. These network shifts often begin three to six months before an employee officially decides to leave, providing amble time for managers to intervene—whether through re-engagement strategies, role adjustments, or retention planning.

Rethinking Succession: Beyond Titles and Performance Scores

Traditional succession planning often misses the mark because it focuses on titles and performance reviews, not real influence.

The best leaders aren’t just high performers. They’re the ones their peers trust, seek out, and follow when things get messy. This is where ONA adds value. It highlights those who broker knowledge, build trust, and bridge silos. These are people not just with skill, but with network capital to move things forward.

Often, the most influential players are the ones we least expect.

Let’s go back to our fictional Maya. Her company was planning a restructuring. On paper, she wasn’t identified as high-potential. But when network analysis revealed her central role in connecting teams and coaching new hires, leadership saw her in a new light. They brought her into strategy sessions to inject new perspectives and develop more efficient rollout plans. They gave her visible roles in onboarding to help new employees integrate. And when leadership positions opened up, she was visible.

Succession isn’t just about promoting from within, but about helping external hires succeed. Technically brilliant outsiders often struggle in their first six months not because they lack skill, but because they don’t yet understand how the culture works.

In Maya’s organization, influence didn’t look the same across every team.

In Engineering, it came from deep technical expertise: being seen as the person who could untangle complex problems when no one else could.

In Sales, it was about presence and persuasion: those who could win over clients and rally peers around a pitch.

In Operations, trust was built on consistency: the quiet employees who always delivered and kept things from falling apart.

Maya’s strength was her ability to navigate these differences. She understood how each group defined credibility and adapted her communication style without losing authenticity. That’s what made her such a powerful connector.

In both internal promotions and external transitions, network analysis helps companies move past subjective instincts to make smarter, more strategic leadership decisions.

Why M&A Fails Without Network Integration

Mergers and acquisitions—where I first started working with ONA—don’t typically fail because of bad strategy or even culture clashes. They fail because of a lack of integration at the human level.

Traditional M&A playbooks focus on financials, product alignment, and leadership structure. But they often overlook the invisible influence networks that determine whether employees collaborate in a way to bring these strategies to fruition.

Take the 1998 Daimler-Chrysler merger. The failure wasn’t only about cultural mismatches between the German and American automakers. Reports suggest that years after the merger, employees continued operating in silos. Their collaboration patterns stayed separate, and a unified network never formed. Had the company identified informal influencers and connectors early on, they potentially could’ve built cross-company bridges and accelerated integration.

More recent deals suggest that companies are learning from past mistakes. Microsoft’s acquisition of LinkedIn in 2016 has often been cited as a smoother integration. Microsoft gave LinkedIn operational autonomy, while gradually connecting capabilities and systems over time. While there’s no public proof that ONA was used, Microsoft’s interest in workplace analytics suggests they likely considered internal networks as part of the strategy.

Today, private equity firms are increasingly using network analysis to assess acquisitions. By mapping informal influence structures, they can identify whether a company's operational strength is deeply embedded or overly reliant on a few key individuals. This approach helps avoid post-acquisition surprises such as discovering that much of a company's value "walks out the door".

Measuring Inclusion Beyond Headcounts

Traditional diversity metrics count representation but miss inclusion. Network analysis reveals whether employees are truly integrated into influence networks or remain isolated on the periphery. Research consistently shows that underrepresented groups often have fewer network connections despite similar qualifications. Not because of ability but because of systemic barriers to relationship formation.

Major companies now use network analysis to ensure diverse employees are integrated into influence networks. They identify where certain groups or individuals are isolated and create cross-functional projects, mentorship programs, and collaboration spaces designed to build connections.

Getting Started: How to Bring Network Thinking Into Your Org

Implementing network analysis doesn’t require a massive investment or a company-wide overhaul. It starts with intention.

1. Start with a Hypothesis

At its core, ONA is data, which is only as powerful as the question you’re trying to answer. For instance, let’s say you suspect a decrease in workplace collaboration, something a real client of ours noticed after a period of growth.

Expansion of sites and headcount made it tougher to connect with new employees

Location-based silos limited communication opportunities to share knowledge

Trust was diminished across sites as few opportunities to connect existed

2. Validate with Existing Data

ONA is a powerful tool, but thrives in cultural nuance. In order to construct a target assessment, we leverage existing data or create light-weight studies to confirm initial observations. Email metadata, calendar invites, messaging tools, and targeted listening sessions can paint an initial picture of your network. But proceed with caution. Automated tools can show who's connected to whom, but not influence.

As one leader put it, “Yes, she’s in every meeting but she never says a word.”

Raw connection doesn’t equate to influence. Complement these tools with qualitative insights to begin to understand the role that trust, credibility, and shared history play in the organizational fabric.

3. Pilot Before You Scale

Choose a team or department as your first test case, especially one experiencing collaboration pain. This focused approach lets you:

Refine your methods

Demonstrate quick wins

Build credibility across the org

From there, expand to broader areas of the business.

4. Blend Metrics with Human Insight

Graphs show structure. But understanding why connections exist and how work gets done requires behavioral understanding. Pair network data with surveys, interviews, or team workshops. These insights help explain nuance, such as structural holes, hidden talent, and provide necessary context behind the lines connecting nodes on a graph.

That’s why ONA pairs so well with behavioral economics, my background. ONA shows us what the landscape looks like; behavioral economics informs us on how to design it to elicit a specific outcome.

5. Choose the Right Tools

Enterprise-grade platforms offer robust functionality, but smaller orgs can start with all-in-one SaaS platforms like Polinode. Choose tools that align with your goals, not the other way around.

6. Move from Mapping to Action

The goal isn’t just to visualize the network. It’s to improve it along the metrics we discussed above, such as network density. Use insights to:

Bridge silos through cross-functional projects

Recognize and elevate informal influencers

Support onboarding by helping new hires build early connections

When done well, network analysis becomes a tool for transformation, not just diagnostics.

7. Protect Privacy, Always

Organizational network analysis touches on your most valuable asset: your people.

Be transparent about what data you’re collecting and why. Anonymize wherever possible. And always prioritize ethical data use over expediency. Where possible, share the network analysis with decision makers and players alike.

The Future Belongs to the Well-Connected

Network analysis is a strategic tool. The most effective uses go beyond simply identifying the structure; they focus on understanding the human dynamics and designing interventions that enhance collaboration and build resilience.

The companies that succeed won't just analyze networks, they'll actively shape them, using data to foster connection, innovation, and resilience. As work becomes more complex and collaborative, understanding organizational networks is a necessity for survival.

The challenges organizations face today from innovation in a rapidly changing environment to knowledge transfer in an aging workforce are fundamentally network challenges.

The formal organization will always matter. Hierarchies provide clarity, accountability, and efficiency. But beneath that visible structure lies the organization's true operating system: the network of relationships through which information flows, decisions are made, and work that gets visibility.

The future of work belongs not just to those who manage well but to those who connect well.

References

Moreno, Jacob Levy (1934). Who Shall Survive? A new Approach to the Problem of Human Interrelations. Beacon House

Burt, RS (1992). Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition. Harvard University Press

Burt, RS (2004). The Social Capital of Structural Holes. The New Economic Sociology: Developments in an Emerging Field. Princeton University Press; 2004. p. 148-189.

Cross R, Parker A (2004). The Hidden Power of Social Networks: Understanding How Work Really Gets Done in Organizations. Harvard Business School Press

Freeman, LC (1979). Centrality in Social Networks: Conceptual Clarification. Social Networks. 1(3):215-239.

Granovetter, MS (1973). The Strength of Weak Ties. Am J Sociology. 78(6):1360-1380.

Krackhardt D, Hanson JR (1993). Informal Networks: The Company Behind the Chart. Harv Business Review. 71(4):104-111.

Kumar, et al (2018): MIS2: Misinformation and Misbehavior Mining on the Web.

Milgram, S (1967). The Small World Problem. Psychology Today. 2(1):60-67.

Radcliffe-Brown, A.R. (1952). Structure and Function in Primitive Society. Free Press.

Erdős, P., & Rényi, A. (1959). On Random Graphs I. Publicationes Mathematicae.

Euler, L. (1736). Solutio problematis ad geometriam situs pertinentis. Commentarii Academiae Scientiarum Imperialis Petropolitanae.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In Richardson, J. (Ed.) Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. Greenwood Press.

*Since you’re still here, you may be interested in seeing Organizational Network Analysis in action. I wrote about our partnership with a healthcare facility that was struggling with inconsistent processes across several of its sites. The study reviews how we used network science to implement novel strategies that uncovered broken communication channels, innovation islands, and the hidden influencers that brought the entire firm back together.

You can find that story here on the 3Fold Outcomes Substack:

Love this article and how it explains that the flow of information within a business can be more valuable than the hierarchy of the business. One thing i’m curious about is how movement along the hierarchy of an organization might change the social capital of an employee like maya. Does she benefit more from staying in her current position than accepting a promotion where the hierarchical structure might move here further away from the teams that she has built these bridges with?