Talent That Endures: Using ONA to Retain Critical Contributors Through Uncertainty

Mapping influence to make smarter, more resilient people decisions.

Amid evolving markets and growing complexity, knowing who drives your organization forward is more vital than ever. Even absent a formal recession, instability prompts organizations to act more cautiously—tightening investments, revisiting strategic priorities, and, in some cases, reevaluating their workforce.

In these moments, the question is not only how to move forward, but who should move forward with the organization. Traditional evaluation methods—relying on titles, tenure, and performance reviews—often overlook individuals who drive collaboration, culture, and execution behind the scenes. Organizational Network Analysis (ONA) offers a quantitative approach to identifying these influential contributors, enabling companies to make better-informed talent decisions and avoid costly mistakes.

Why Traditional Methods Fall Short

Organizational charts and performance metrics provide only a partial view of a company's true structure. Research by Cross and Prusak (2002) highlights that many of the most influential employees are not identified by formal hierarchies or traditional evaluations. Their work illustrates how formal authority, assigned by organizational structure, often diverges from the informal authority earned through trust, collaboration, and relational influence. In many cases, individuals with the greatest operational impact exert influence through social and political networks that are not visible on an organizational chart.

This hidden influence often goes unnoticed because leaders fall prey to cognitive biases. Authority bias can cause them to overvalue formal titles, while availability bias leads them to prioritize the most visible individuals.

How ONA Enhances Decision-Making

ONA maps the social and political networks that underpin communication, trust, and collaboration within a company. It identifies individuals who connect disparate groups, hold trust-based influence, and facilitate knowledge flow across silos. Through quantitative measures such as degree centrality (the number of direct ties an individual has) and betweenness centrality (the extent to which an individual connects otherwise isolated groups), ONA provides empirical insight into organizational dynamics.

These "power brokers" are often invisible in traditional evaluations yet are essential for organizational resilience, particularly when leaders are tasked with achieving more with fewer resources. By surfacing these individuals, ONA enables leaders to base decisions on a fuller, data-driven understanding of the networks that sustain organizational performance.

The foundations of ONA stem from early mapping techniques applied in diverse settings, including Krebs' (2002) work analyzing social networks within covert groups, highlighting the power of relationship structures over formal hierarchies.

Applying ONA to Talent Decisions

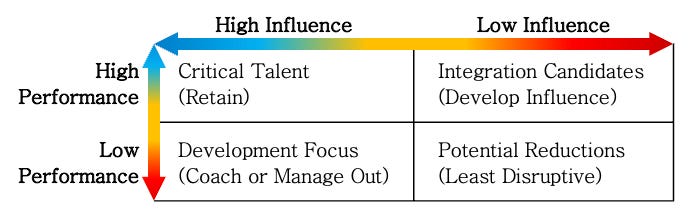

Using ONA in combination with traditional performance data, leaders can create an initial segmentation of employees into four categories, providing a starting point for deeper talent discussions and more informed decision-making.

Figure 1: Influence–Performance Talent Map

Note: While this framework focuses on direct influence, it is equally important to consider relational access. Employees who are closely connected to critical power brokers, even if they do not command high direct influence themselves, may play vital roles in maintaining organizational resilience and operational effectiveness. ONA enables leaders to surface both direct influencers and strategically positioned connectors, creating a more complete view of talent dynamics.

Performance metrics alone offer an incomplete view of an employee's value. Direct influence acts as a critical amplifier—enabling individuals to translate their expertise into broader organizational outcomes. Without it, even top performers may find their efforts isolated and less impactful.

While this framework focuses on direct influence, it is equally important to consider relational access. Employees who are closely connected to critical power brokers, even if they do not command high direct influence themselves, may play vital roles in maintaining organizational resilience and operational effectiveness. ONA enables leaders to surface both direct influencers and strategically positioned connectors, creating a more complete view of talent dynamics.

This broader relational perspective is especially vital for service- and knowledge-driven industries, where success depends not just on individual excellence but on the ability to activate and mobilize networks. Access to influence ensures that ideas are not only initiated but carried across teams, accelerating innovation and sustaining change at scale.

Why Leaders Miss Critical Influencers (Behavioral Blind Spots)

Even with the best intentions, leaders frequently overlook critical contributors due to predictable cognitive biases. Behavioral economics highlights several common traps: overconfidence bias leads leaders to assume they already know who the key people are; status quo bias results in favoring familiar individuals over emerging influencers; and loss aversion drives protection of legacy roles rather than investment in rising talent. These biases distort how leaders perceive influence within their organizations, especially under conditions of uncertainty.

ONA mitigates these blind spots by surfacing objective relational data, enabling leaders to make better-informed and more resilient talent decisions without over-relying on intuition.

The Risks of Overlooking Influence

The departure of key network connectors can trigger a cascade of negative outcomes. Losing these individuals often leads to knowledge silos, breakdowns in collaboration, and prolonged decision cycles. These effects cumulatively degrade productivity, innovation, and resilience, often at a scale disproportionate to the number of individuals lost. Experience suggests that important projects can be significantly delayed when critical employees exit, with cascading impacts on strategic initiatives and revenue goals.

Flight risks often manifest long before formal resignation. Employees who display declining network centrality, form fewer new connections, or disengage from established relational ties signal potential departure. ONA enables early detection of these patterns, allowing organizations to implement targeted retention strategies and reinforce engagement through relationship-building initiatives. Addressing flight risks becomes especially critical during periods of uncertainty, when the most capable employees are often the first to exit.

Proactive Planning Beats Reactionary Moves

Companies often respond to instability with reactive decisions based on incomplete information. Proactively applying ONA enables early identification of key talent, supports targeted retention strategies, informs succession planning, and mitigates the risk of critical knowledge loss.

Behavioral economics complements ONA by guiding leaders in crafting interventions that resonate with employee psychology. Research in choice architecture and signaling theory suggests that certainty—through clear communication, visible investment, and tangible recognition—is pivotal in securing employee retention during uncertain times (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008).

Mergers and Acquisitions and the Critical Role of ONA

Mergers and acquisitions exemplify the risks of ignoring social and political networks. Although precise figures are difficult to confirm, anecdotal evidence suggests that productivity declines between 30% and 50%, largely due to the disruption of key relational ties. High-value employees, sensing instability, frequently exit within the first year.

Experience suggests that the departure of critical connectors during M&A can delay strategic initiatives and weaken organizational cohesion. While specific outcomes vary, organizations that fail to identify and retain these power brokers often face prolonged integration timelines and weakened organizational unity.

In private equity contexts, early application of ONA has enabled firms to retain critical connectors who stabilize the integration process, identify and engage future leaders early, and minimize cultural fragmentation often accompanying mergers.

Embedding ONA into Organizational Strategy

For organizations seeking to build resilience systematically, ONA must become an ongoing capability rather than a crisis-driven tool. Leading organizations increasingly embed ONA into business practices such as leadership development, identification of emerging innovation hubs, and cultural health checks. Monitoring network evolution allows companies to detect early signs of fragmentation, assess team resilience, and proactively manage succession pipelines.

Conclusion

ONA does not supplant leadership judgment; rather, it enhances decision-making by revealing hidden structures, surfacing blind spots, and providing a richer, more objective foundation for evaluating talent.

In an environment where every decision carries amplified consequences, the integration of Organizational Network Analysis with behavioral strategy empowers companies to make smarter, more human-centered decisions—decisions that safeguard both business performance and organizational culture.

Organizations preparing for change—or simply aspiring to build greater resilience—should invest now in understanding the real networks that underpin their success. The organizations that invest in understanding these hidden networks today will be the ones best positioned to lead, adapt, and thrive through tomorrow’s evolving challenges.

References

Cross, R., & Prusak, L. (2002). The people who make organizations go—or stop. Harvard Business Review, 80(6), 104–112.

Krebs, V. (2002). Mapping networks of terrorist cells. Connections, 24(3), 43–52.

Pentland, A. (2014). Social Physics: How Good Ideas Spread—The Lessons from a New Science. Penguin Press.

Krackhardt, D., & Hanson, J. R. (1993). Informal networks: The company behind the chart. Harvard Business Review, 71(4), 104–111.

Krug, J. A., Wright, P., & Kroll, M. (2014). Top management turnover following mergers and acquisitions: Solid research to date but still much to be learned. Academy of Management Perspectives, 28(2), 147–163.

Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Yale University Press.

Thanks for sticking around until the very end. While you’re here, you may be interested in reading the origin story of organizational network analysis and more about its modern-day applications. In the below story, I take you back to the 18th century to witness the creation of graph theory, the integration of archeology and psychology in the 20th century, and the social and organizational implications. You can find it here on the 3Fold Outcomes Substack:

The Hidden Organization: Mapping the Networks That Really Run Your Company

Do some mid-level employees quietly hold more power than their C-suite executives?

Really informative post again. Love the nuance about influencers and key connectors and their importance which is often ignored.